I’m no acolyte of technology writ large. Heck, I don’t even own my own cell phone and am currently writing a manuscript about the intellectual woes of Microsoft Word. Having said that, I cannot deny the power and utility of some technologies. In this post, I’ll tell you which ones I have in mind exactly and why I think they’re worth taking the time to pick up.

Storage, Notetaking, & Citation Software

By a long shot, the tool that has saved me the most time and energy is notetaking/citation software. These days, there are many on the market, a useful comparison of which can be found here. I confess that as far as comparisons go, I have only listened to presentations on the subject, without test-running all the options myself. When I was making my transition from Microsoft folders to a notetaking program, I decided in a rather helter-skelter fashion on Zotero. Nevertheless, I’ve been more than pleased with the program. In fact, I don’t think it’s really possible to appreciate the power of this technology until you see it in action. Even so, allow me to summarize my favorite of its features.

Citation

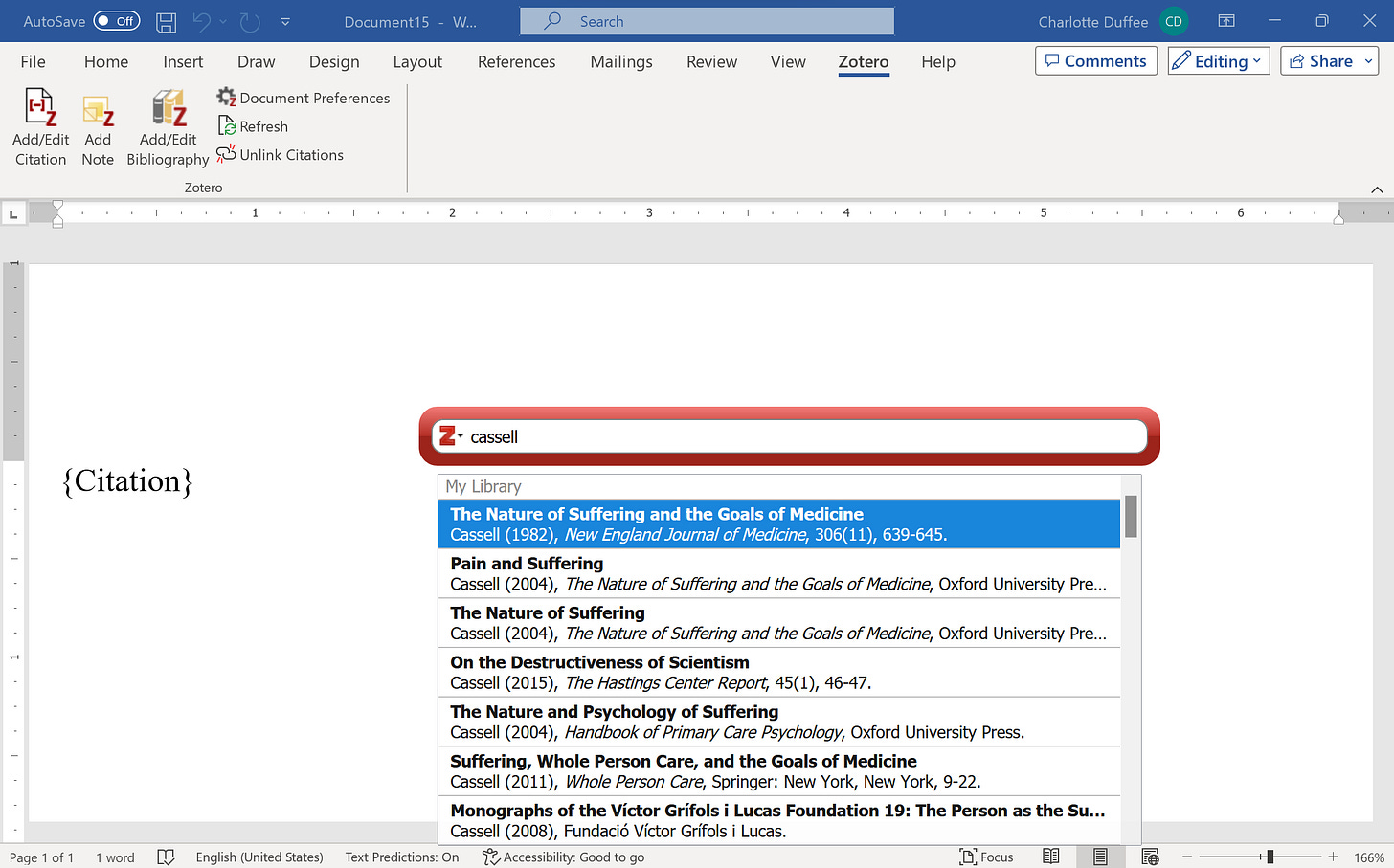

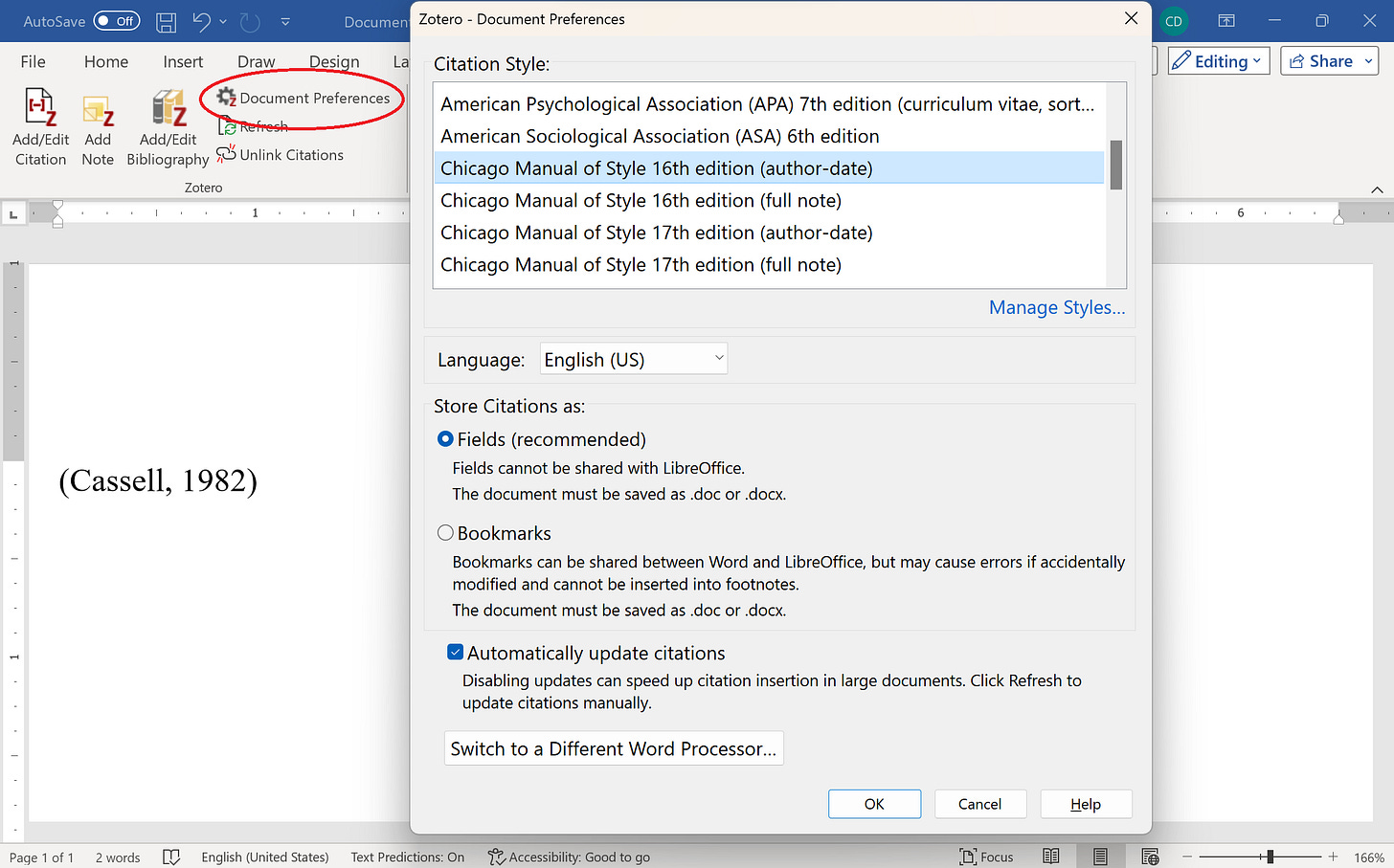

CITING: When you download Zotero, it automatically adds a new button to your Microsoft Word processor, allowing you to search for sources in Zotero and cite them automatically, as in the first image below. It’s easy to change citation styles, too—say, for a rejected manuscript you’re keen on submitting elsewhere. All you have to do is select the ‘Document Preferences’ button in the top left hand corner, per the second picture.

CREATING BIBLIOGRAPHIES: Perhaps most impressive of all, with the click of the “Add/Edit Bibliography” button (also pictured above) Zotero can automatically generate a bibliography from the sources you've cited in-text.

CREATING SYLLABI: Relatedly, you can export all the sources in a folder by highlighting (Ctrl+A) and copying (Ctrl+Shift+C) them all. Paste them in a Word doc (Ctrl+V) and voila! Now you have the meat and potatoes of a syllabus in one second flat.

Notetaking and Storage

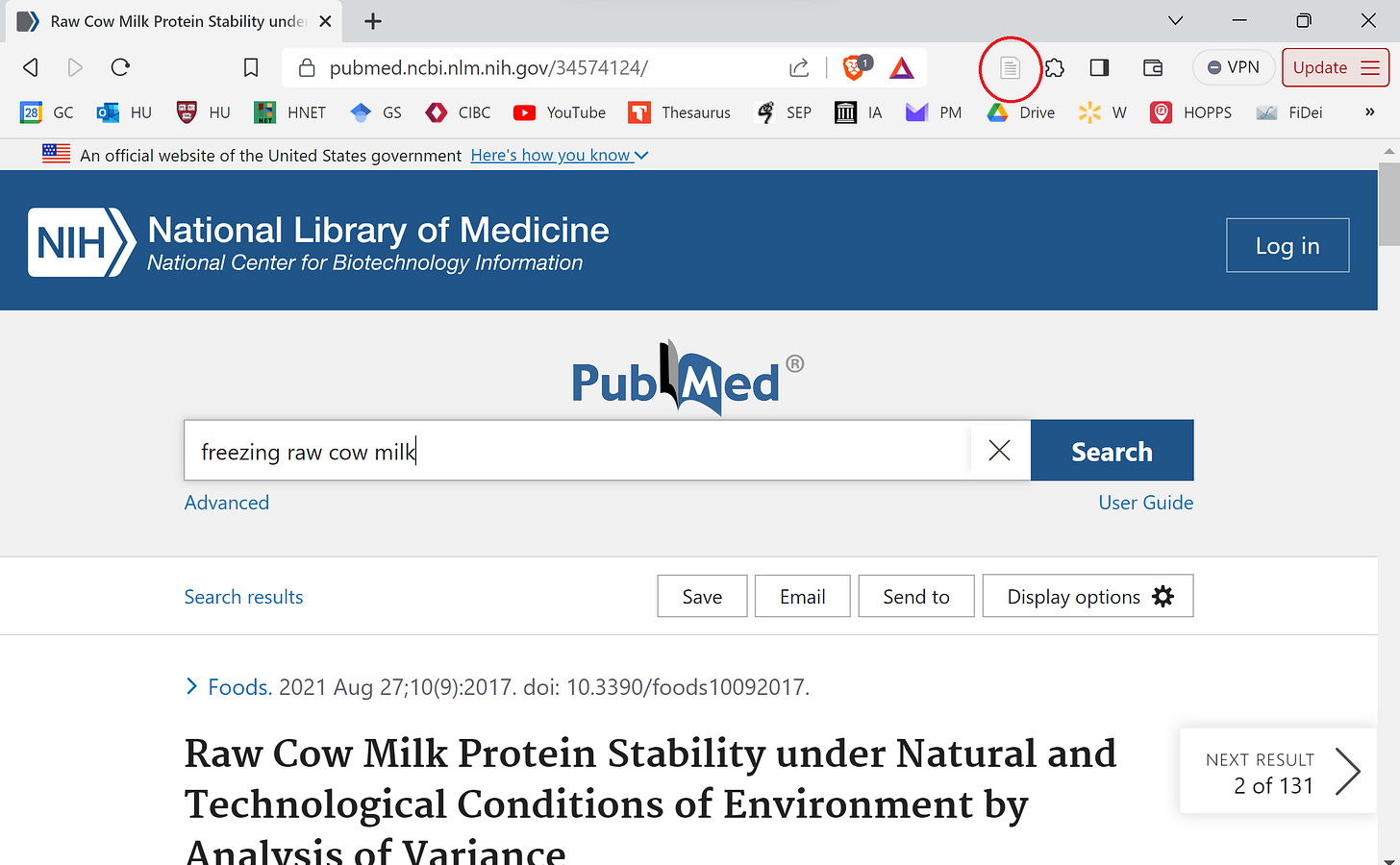

OBTAINING NEW TEXTS: To download new literature, Zotero comes with this connector that can be added to your web browser (for example, see the icon circled in red below). With a click of this button, it will save your reading and all of its bibliographical information, which it takes down pretty accurately in my experience.

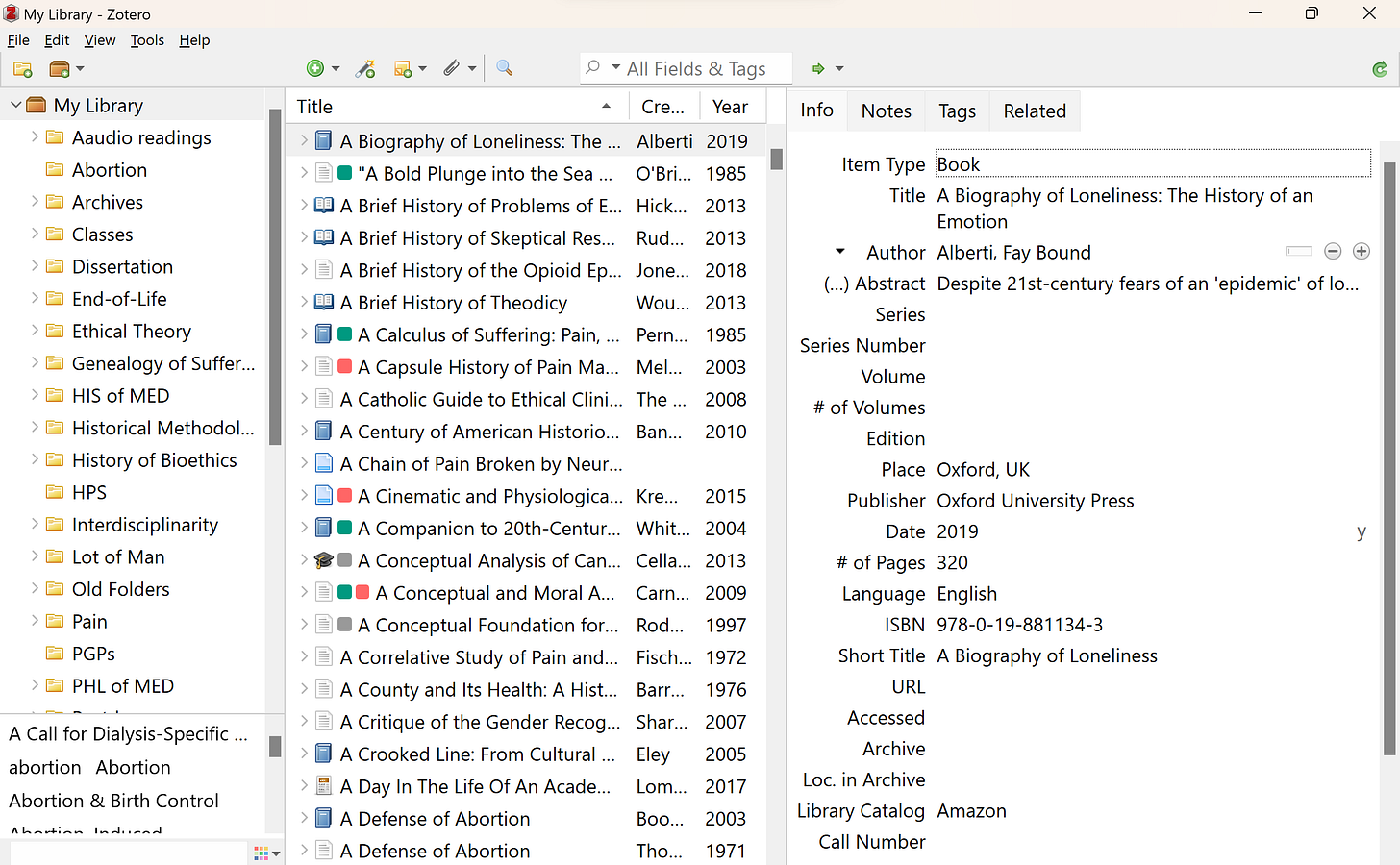

TAKING NOTES: Gone are the days of loose-leaf papers and marginalia miscellany. At long last, you can now keep everything you need in one spot, a Zotero library. Each record in it includes a PDF of your literature, its bibliographic information, tags, and notes you’ve taken—all of which can be organized into separate folders or shared across libraries for collaboration with other colleagues. You can also customize the interface of your library. Here’s mine:

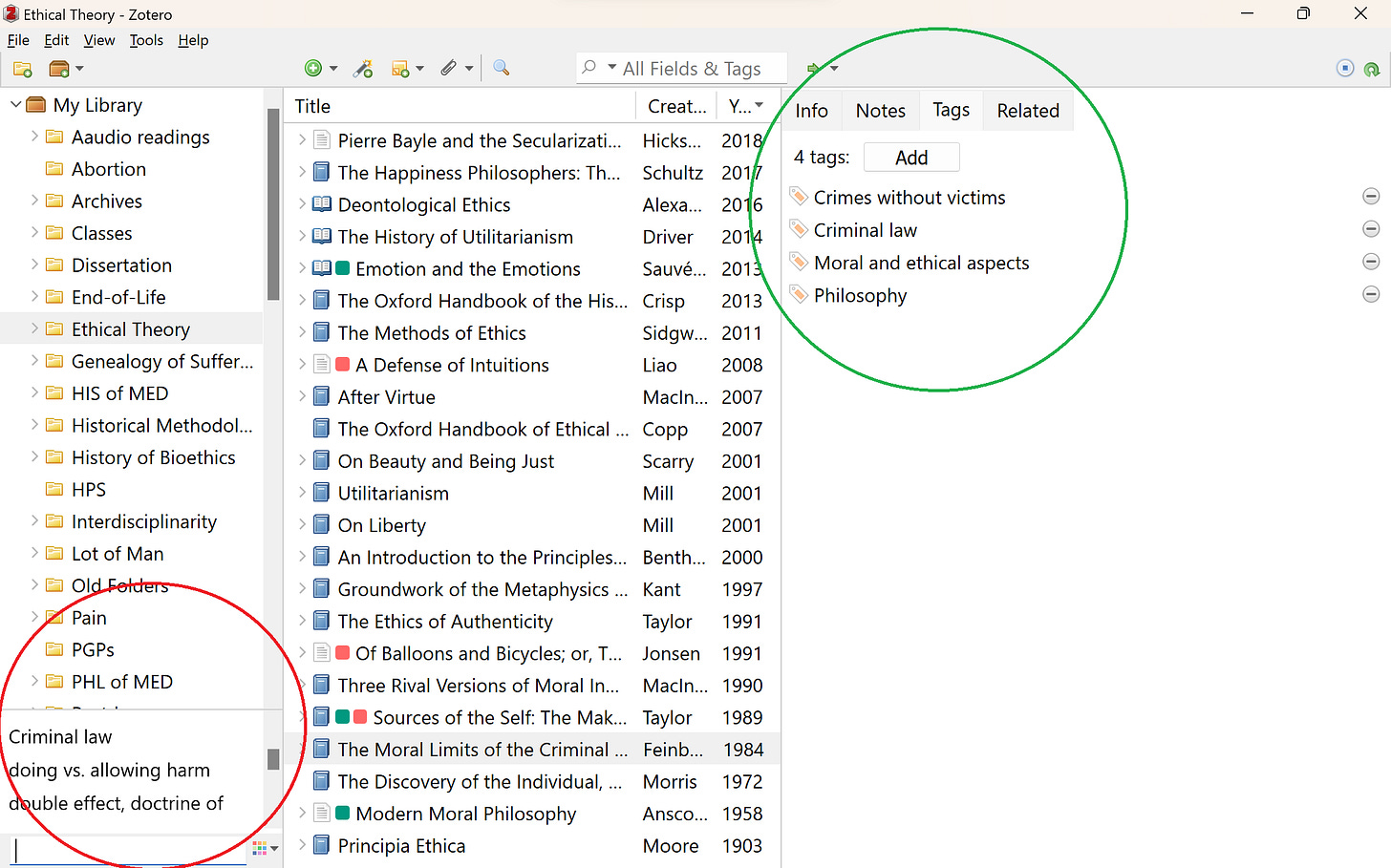

SEARCHING YOUR NOTES: All at once, you can perform word searches across your entire library, as well as in each folder. That includes all the records of all your readings and every note you have ever drafted. Very often, I can only recall a snippet of an interesting insight I read somewhere, that I know is in my notes but not which one. A quick search pulls all that information up and has saved me the trouble of finagling, googling, etc., to track down quotes, citations, and the like. You can also tag your notes to build these connections pre-emptively. Also, when you download texts, the publisher’s tags already come with it. For an example, the green circle below shows you how Joel Feinberg’s “The Moral Limits of the Criminal Law” automatically appears in my Zotero library, while the red circle highlights where to search for tags alone (as opposed to the “All Fields & Tags” search bar at the top of my library):

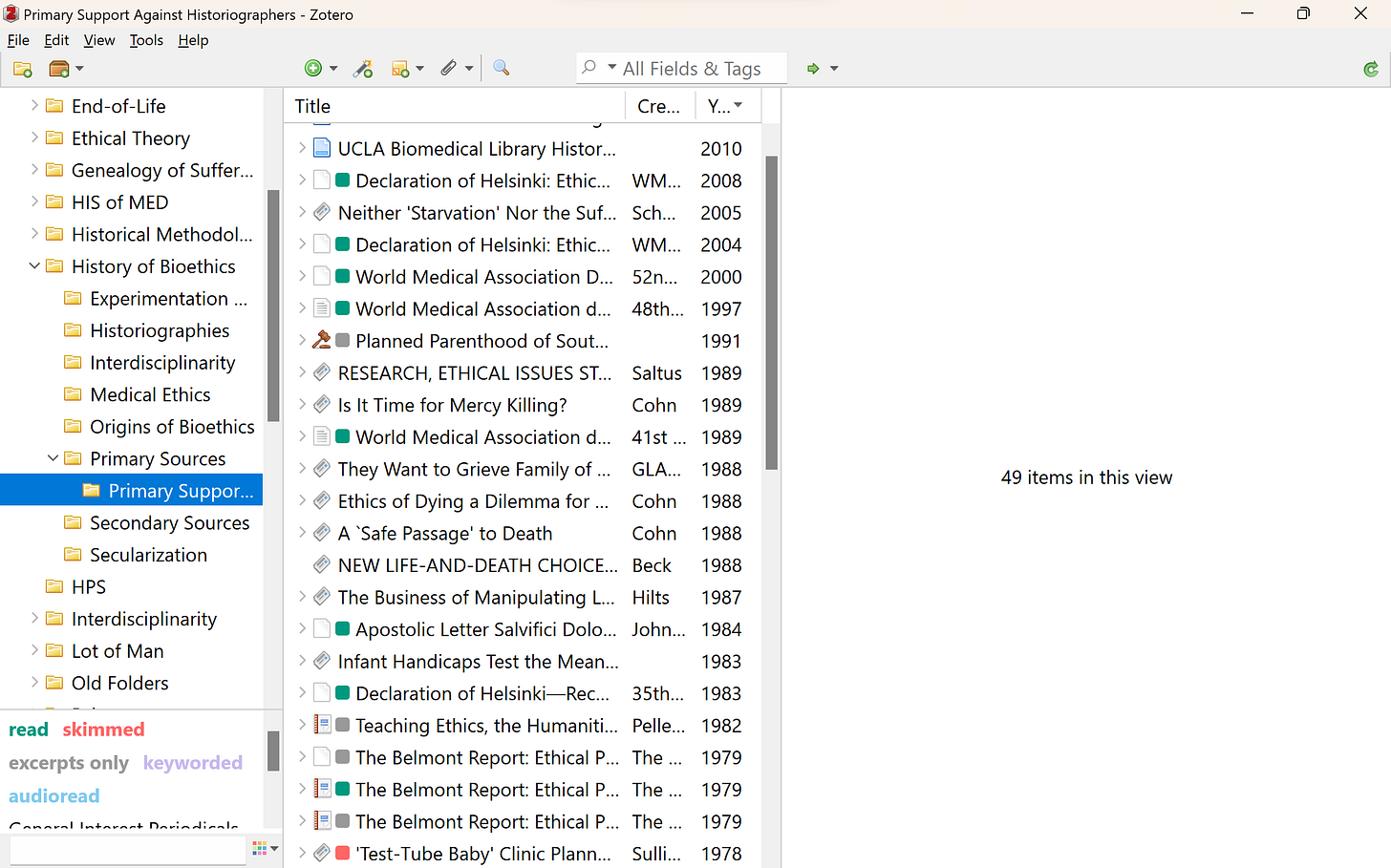

TRACKING YOUR READING PROGRESS: On the subject of tags, you can right-click your tags to color-code them, which I have found incredibly useful as a tracking system for the sources that are unread, read, skimmed, excerpted, keyworded, and so on. This has proved especially handy when dealing with large volumes of literature across multiple projects. For example, below is a folder in my library, where you can see in the bottom left corner the meaning I have assigned to each color. The colors, in turn, appear as little squares beside the title of my items. In my library, every item without a color is presumed to be unread.

SAVING AND SYNCRONIZING YOUR NOTES: Everything is saved locally on your device for use in offline environments. But once you go online, your entire library is automatically synchronized and periodically re-synchronized into Zotero's backup cloud. Never again need you fear the blue screen of death. What’s more, this is true across all of your devices. That includes smartphones, since Zotero has an app version as well. I have it downloaded on one of my husband’s phones that I borrow (see my post on semi-luddism for an explanation of this circuity). If I have a long car ride or some other menial activity to do, I send readings from Zotero to my audio-reading app to work while I’m on the fly. And now, more about reading apps!

Finding Literature in the First Place

It can be difficult to stay on top of the latest literature, but new technologies make the task more manageable. Several scholars use RSS feeds, such as Feedly, with reader apps like NetNewsWire. I myself am still working through the best approach, but so far I’ve set up alerts in Google Scholar attached to an email I set up just for academic work. Having a separate email protects the rest of my life from too much academic intrusion, while preserving my alerts across whatever institutional changes I may experience. By pulling scholarship based on keywords rather than discipline, I can be sure I’m getting a panoptic view of what scholars across the academy are discovering on my research topics.

Nevertheless, keeping a closer eye on research in one’s primary field is crucial. Journals often have email sign-ups for this purpose, but discipline-specific literature collection platforms might also exist in your field. In mine, for example, I have created a feed on Philosophy PaperBoy.

Reading & Editing

As just mentioned above, reading apps help you make mindless tasks more mindful. Just think of it: now you can justify exercising more by taking Dostoevsky on the treadmill! Actually, upon reflection, that’s probably not be the most enticing example. But you get the point.

In my experience, two things matter most if you want audio-reading to work for you. First, you must select the right kinds of things to read in this format. Not every scholarly text will fit that bill. As a philosopher and historian, I have really only found success audio-reading narratives: that includes prose fiction and some histories (not ones that require a lot of scrutiny of a book’s end matter). I would caution against attempting dense philosophy (with the exception of Nietzsche and others who are hardly intelligible half the time anyways). Also be sure to avoid literature with graphs/tables/charts, every detail of which the text reader will attempt to read to you.

Second, you must, must, must have a good text reader. Anything too robotic, or with sub-standard AI/OCR capacities, will either muddle the pronunciation of words or skip them altogether. In both cases, you’re setting yourself up to miss potentially vital information. It’s too taxing on your attention to monitor the author’s arguments and the performance of your text reader.

Of the programs I have tested, Voice Dream is the best. It’s $25 in the Apple store and worth every penny. It can read everything from books to PDFs to Word Docs to webpage HTMLs. The intonation is great, the accent options are plentiful, and the pronunciation is pretty good. Note, though, that for some texts, it mistakes ‘f’ for ‘s.’ So, ‘suffer’ will sometimes sound like ‘susser,’ for instance. It’s a bit annoying but not a huge deal once you catch on.

As a quick aside, I have found audio-reading incredibly useful for late-stage editing. We always tell students to read their own work out loud before submitting it, but as scholars we can sometimes get too close to the thing to really read it freshly—especially when you’re nearing the end and can probably recite some sections by heart. To fix this issue, I change screens so that I’m not looking at my text and then feed one of my drafts to Voice Dream. Listening to my own writing in this way has helped me catch stylistic kinks, typos, and other errors that went unnoticed. When I come across one of these problems, I pause the reader, switch to my draft screen, make the edit, and then return to the reader.

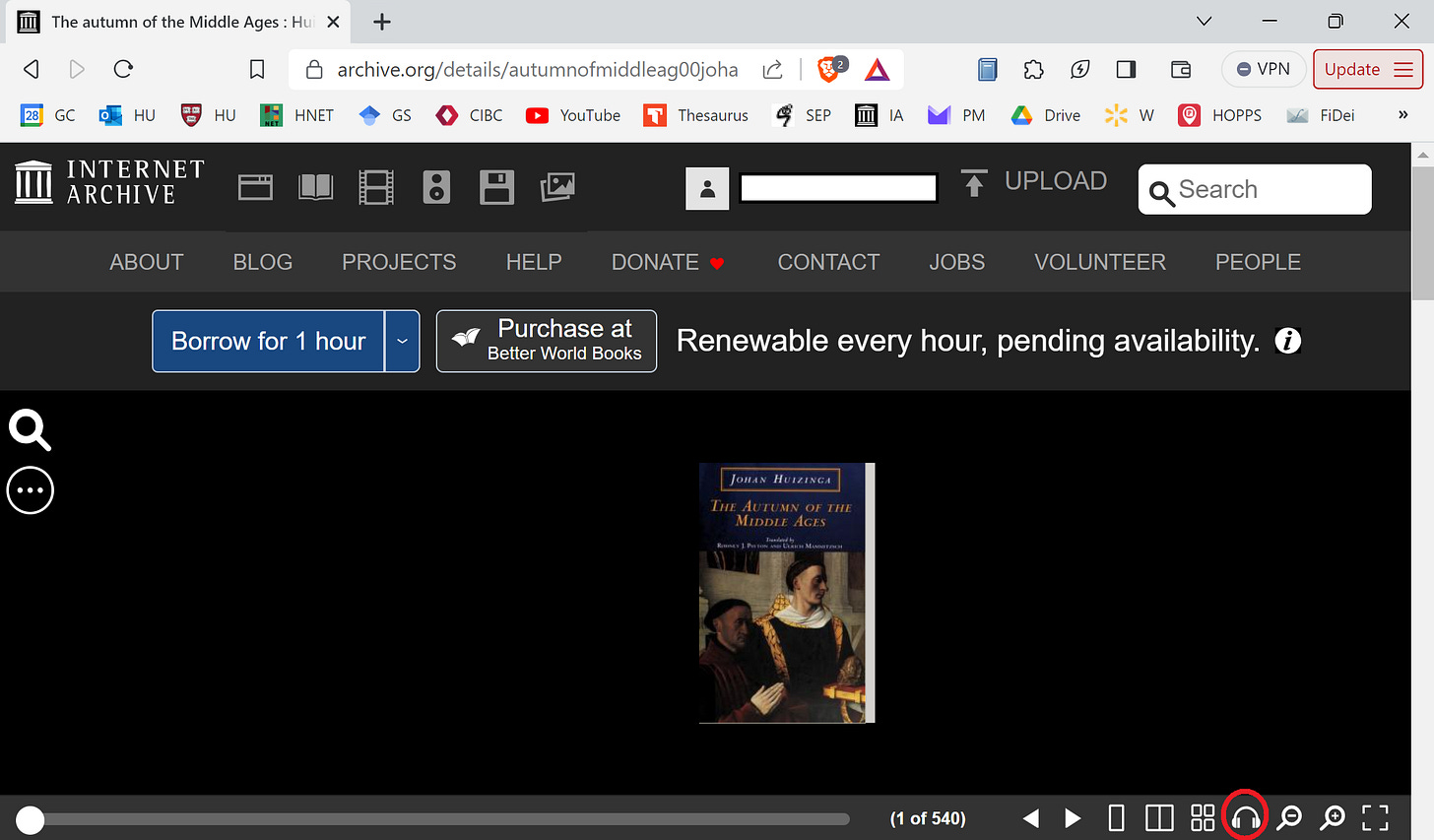

Of course, one problem for Voice Dream is that many of the texts we want to listen to don’t exist digitally—at least not in formats that are legally downloadable. One way around this is Internet Archive. While you can download a lot of books as Voice Dream-compatible PDFs/HTMLs at the bottom of the page on Internet Archive, not all of them have this feature; many can only be borrowed for repeated hour-long intervals. A lot of scholars know this already. But what they might not know is that Internet Archive can read you these texts. Simply click the headphones icon in the platform’s bottom right-hand corner (see circled image below). Do note that the pronunciation and speed-control are sometimes wanting.

Conclusion

I hope this detailed run-through has piqued enough curiosity for you to consider giving these tools a try. I cannot reiterate enough just how useful they’ve been to me. In combination with other major changes, these tools have helped me just about double my productivity. And that means double the time to spend with my kiddos.